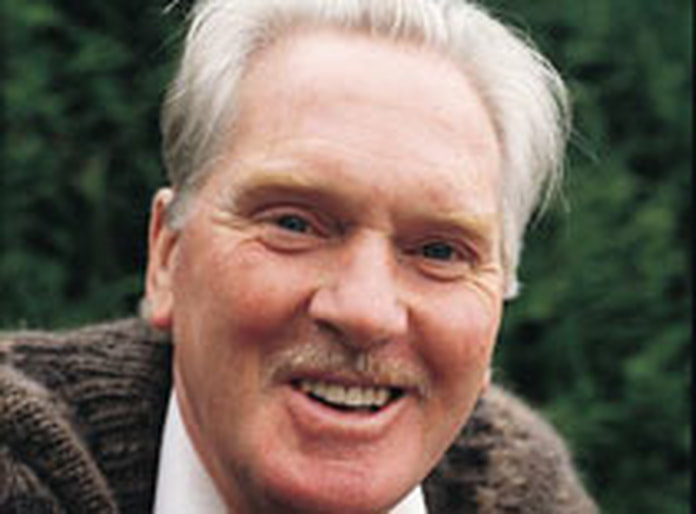

"There are a number of times in our lives when we will get lost and stray from the right path. If we wander aimlessly about in the hope of finding our way back, we may fall lucky, but I suspect that we will probably require the help of someone else who happens to be around at the time.

I was born the eldest of seven children where most family income went on food. Between the ages of seven and eleven years, I honed my stealing skills as well as I could. My life of theft was brought to an abrupt halt at the age of eleven when I was run over by a large milk float on Third Avenue, Windybank Estate. I almost lost my life, was in the hospital for ten months, and when I was discharged, I was unable to walk for the next three years. My stealing stopped just like that! It's hard to steal if one cannot walk, let alone run away!

At the age of fifteen years, I was to commit my last act of theft and I can honestly say that I have never stolen since. My final act of theft involved stealing apples from display crates outside Mr Northrop's, the greengrocer's shop on Fourth Avenue, Windybank Estate. Mr Northrop saw me in the act from inside his shop, recognised me and threatened to tell my father when he next saw him. I knew that once dad found out I'd been stealing, I wouldn't be able to sit down for another three weeks, and I might not be able to walk for 'another' three years.

For the next two weeks after my theft from the greengrocer's shop, I was on tenterhooks. One evening I saw Mr Northrop approach our house. Dad was in, but not mum. My fear level soared. Sensing I'd done some wrong based on past experience, my father said, 'Hello Mr Northrop. What's our Billy been up to now?' The kindly greengrocer smiled and said, 'His mother called into my shop last week and asked if I could give him a Saturday morning job to keep him out of trouble and earn himself a few bob. Well, he can start next Saturday at 8am until noon, packing and weighing potatoes for two shillings and sixpence, if he wants to?'

My dad replied, 'It's nowt to do with him. Take it from me, Mr Northrop, he wants to!' I stayed in that job for the next two years, even after I'd started working full time in a Cleckheaton spinning mill, 'Bulmer and Lumbs'. At a time in my life when I'd lost my way, Mr Northrop had been the one to help me find it. He'd not only kept the knowledge of my theft from my parents, but he never raised the matter thereafter. He is undoubtedly the one person who was most responsible for me eventually going straight.

Sixteen years later, I'd turned poacher to gamekeeper and worked as a Probation Officer in Huddersfield. I loved that job and it allowed me to facilitate giving 'second chances' for many other offenders. There was one offender who I will never forget. His name was Bernard and I met him part way through his second two-year Borstal sentence. In those days, most two-year sentences to borstal meant that one served the full two years minimum. If the inmate maintained good behaviour, he was released after two years. If he demonstrated bad behaviour during the course of his sentence, he would be given additional time to serve. Bernard was released from his first two-year borstal sentence after he'd served almost three years. Incidentally, in those days of the early 70s, repeat offenders would be given a Borstal Sentence for minor thefts.

Bernard had been abandoned at birth. He'd never known either parent and had been reared in Children's Homes all his life. I was to work with Bernard over a seven-year period, during which time he would serve two Borstal sentences, breach two Probation Orders and serve a further two sentences in a Youth Custody Prison and one sentence in an adult prison. For the first two years of my contact with Bernard, I visited him monthly inside borstal and then prison. Each visit would last an hour and it never once varied in two years. I would talk, Bernard would sit there and never once speak one word. I persisted, however, in my belief that he would one day do me the basic courtesy of at least replying to something I said to him.

Two years down the line, my widowed mother-in-law was dying from cancer and so we brought her back to our home to die. The night before my next visit to see Bernard in Thorp Arch Young Offenders Prison my mother-in-law died and I spent half the night phoning around friends and family and making all the necessary arrangements. When I visited Bernard the next day I was tired and had missed much sleep. Bernard remained his usual silent self and after half an hour of silence, I uncharacteristically exploded. I called him 'selfish', and reminded him that in two years of faithfully visiting him he'd never uttered one word; not even a simple 'Thank you.' I rose to leave the visiting cell and behind me, I heard, 'Thank you, Mr Forde, for visiting me today. Please don't stop coming!'

I worked with Bernard over the next five years, but whatever lodgings or job I got him, he soon left them. He continued to steal at every opportunity and the only progression in our relationship was that he was now speaking to me. I was with Bernard all the way through his second and third Prison sentence. After the third prison sentence, Bernard seemed to disappear from the radar. I often looked up the details of the day's court results in 'The Huddersfield Examiner' and was relieved to find Bernard's name absent from it. I hopefully assumed that unless he'd moved areas or had changed aliases, some mighty change had occurred in his life.

About seven years after I'd previously seen Bernard, I was walking through Huddersfield one day and a voice from behind said, 'Mr Forde.' I turned to see a smiling-faced Bernard grinning from chin to chin. He was holding a five-year-old boy in one hand as he pushed a buggy with a three-year-old child in it. He introduced the young woman he was with as his wife of four years' standing. She looked to be heavily pregnant with their next child. Bernard proudly told me that he had gone straight since we'd last seen each other. He thanked me for being in the right place at a time when he was lost and needed to find the right path again.

I looked at Bernard and said, 'The man you really need to thank, Bernard, is a Mr Northrop who used to run a greengrocer's shop on Windybank Estate. Without him coming along at the right time in my life to help me, our paths would probably have still crossed, when we met up on the same side of the prison bars and had become prison buddies.'" William Forde: February 28th, 2018.