"I was born in 1942, the eldest of seven children and though the material circumstances of my early development were poor, my memory never has been. I remember well the first nutritious drink of the day being a child-sized free bottle of milk that the government used to give me at school every morning. I remember the first pair of black shoes I ever wore and although second hand, I was quickly taught by my mother how to make them shine until they reflected my face.

I remember school diners with sago pudding which we patternised in streaks of jam before we dare digest it. I soon learned that those at the top of the table were the ones who served and they got the biggest portions. Being taught in a strict Roman Catholic School, I learnt that God (who was 'absolute'), made the world and everything in it, but during the school day our Headmaster, Mr Armitage decided what information was stuffed inside our heads our heads and made all other rules that governed our conduct.

I can remember my first pair of long trousers, the first bicycle I owned, my first prayer, the first poem I recited and the first song I sung publicly, my first kiss, my first job and my first foray into the secret life of adult pleasures. And yet throughout such learning and memories, I recall that prayer always started and ended my day.

Today as a writer, I frequently write about the things that my late mother could remember about her upbringing and which she would often tell us about whenever we complained that 'life was hard.' If we complained about walking half a mile to the shop for a bottle of milk, she would instantly tell us how she used to walk a return journey of six miles daily to get her milk before she got ready for school. Whatever we experienced, however hard or unpleasant was the task, I was soon to learn that she'd experienced far worse 'with knobs on!'

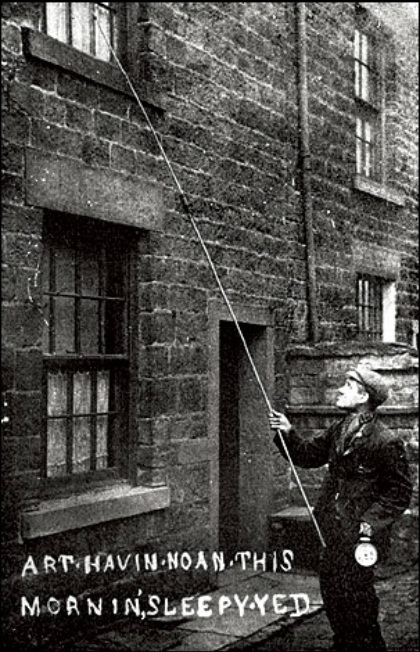

My late father was a miner for a dozen years between the Second World War and the 1950's and until recently, I'd forgotten all about my mother's tales of the street 'Knocker upper' that the miners used to have during the late 1940's to ensure that they didn't sleep in and got to work on time. The 'Knocker upper' would always seem to take it personally if he was unable to rise someone and as he rapped harder and harder on the window pane, he'd yell in a language that all understood, 'Aren't having none of this morning's sleepy eyed.' Those men who worked below ground at the pit face and who arrived after the pit shaft had descended below ground to start their shift would either be sent back home 'without pay' or be allocated a pit-surface job of lesser wage level. I remember the day my father came home and told my mother that the pit was on strike. My mother's reply was, 'But how will I feed the young ones, Paddy?'' The day later my father was the only man at the pit to walk across the picket line. It broke his heart to not join his working comrades, but he put his wife and family first. I do not think that I could ever have displayed such guts. I will always remember the wry smile on his face, when on my 18th birthday, he opened a national newspaper to read about me being elected the youngest textile shop steward in Great Britain. These are just a few of the things I remember and shall never forget." William Forde: August 18th, 2013.